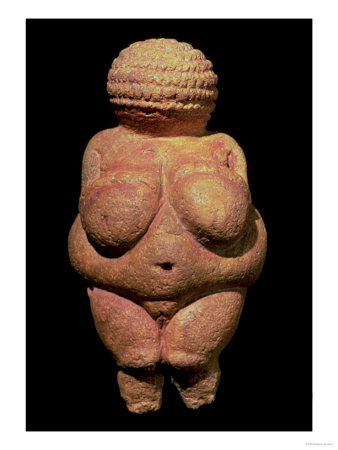

Woman holding a bison horn, from Laussel, Dordogne, France,

ca. 25,000 -20,000 B.C. Painted limestone, approx 1' 6" high. Musée d'Aquitaine, Bordeaux.

The Venus of Laussel was found by the entrance of a cave, a common dwelling place for early humans. Her figure is similar in form to the Venus of Willendorf, with the hips, belly, and breasts exaggerated. Her left hand rests on her seemingly pregnant midsection, whilst her right hand holds a horn. The meaning of the horn is yet unknown and currently debatable. Women and Bison in French Caves Many relief sculptures were found in French caves. One of the most remarkable rock-cut relifs is the Venus of La Magdelaine.

Reclining woman, rock-cut relief, La Magdelaine cave, Tarn, France ca. 12,000B.C. Approx. half life size

This sculpture is typical of many Paleolithic reliefs in that the artist used the natural contours of he stone wall as a basis for sculpting. Another form of Paleolithic relief sculptures are (additive?) mounted clay forms on a freestanding stone.

Two bison, reliefs in cave at Le Tuc d'Audoubert, Ariege, France, ca. 15,000-10,000 B.C. Caly, each approx. 2' long. An artist has modeled two clay bisons, once more in profile, against a freestanding rock. Notice how, as time passed that art has become more and more detailed and realistic.

An Antler Becomes a Bison

As time passes by, stone sculptures became more 'realistic' and detailed. In 12,000 B.C from La Madeleine France, is a newer example.

Bison with turned head, from La Madeleine, Dordogne, France ca. 12,000 B.C Reindeer horn, approx. 4'' long. Musée des Antiquités Nationales

Notice here the details of the antlers, eyes and snout, even the coat of the bison. Notice also, how the bison's head is turned a full 180 degrees, purposely to maintain it in a strict profile.

A Little Girl Discovers Paintings in a Cave An amateur architect, Don Marcelino Sanz de Satuola, and his little daughter Maria were one day exploring caves in his estate, where he had previously found flint and carved bone. That was when Maria had seen the painted beasts.

Bison, detail of a painted ceiling in the Altamira cave, Santander, Spain, ca. 12,000-11,000 B.C Each bison approx. 8' long.

" Materials and Techniques: Paleolithic Cave Painting The caves of Altamira, Lascaux, and other sites in prehistoric Europe had served as underground water channels, a few hundred to several thousand feet long. They are often choked, sometimes almost impassably, by deposits, such as stalactites and stalagmites. Far inside these caverns, well removed from the cave mouths earl humans sometimes chose for habitation, hunter-artists painted pictures on the dark walls. For light, they used tiny stone lamps filled with marrow or fat, with a wick, perhaps, of moss. For drawing, they used chunks of red and yellow ocher. For painting, they ground these same ochers into powders they blew onto the walls or mixed with some medium, such as animal fat, before applying. Recent analyses of the pigments used who they comprise many different minerals mixed according to different recipes, attesting to a technical sophistication surprising at so early a date. Large flat stones served as the painters' palettes. the artists made brushes from reeds or bristles and used a blowpipe of reeds or hollow bones to trace outlines of figures and to put pigments on out-of-reach surfaces. Lascaux has recesses cut into the rock walls seven or more feet above the floor that once probably anchored a scaffolding that supported a platform made of saplings lashed together. This permitted the painters access to the upper surfaces of the caves. Despite the difficulty of the work, modern attempts at replicating the techniques of Paleolithic painting have demonstrated that skilled artists could cover large surfaces with images in less than a day."

Cave paintings, much like the early sculpture, depicted animals still in a strict profile. The animals in that painting don't stand on a common ground line and they don't have a common orientation. they seem to be floating. the paintings have no setting, no background. The painter was probably not concerned with where the animals were. Actually, many seem to be painted randomly, just as figures in space. the reason behind these cloud-like images are still hazy. There are, however some theories.

" Art and Society: Animals and Magic in the Old Stone Age

From the moment in 1879 that cave paintings were discovered at Altamira, scholars have wondered why the hunter-artists of the Old Stone Age decided to cover the walls of dark caverns with animal images. Various answers have been given, including that they were mere decoration, but this theory cannot explain the narrow range of subjects or the inaccessibility of many of the paintings. In fact, the remoteness and difficulty of access of many of the cave painting sites and the fact they appear to have been used for centuries are precisely what have led many scholars to suggest that the prehistoric hunters attributed magical properties to the images they painted. According to this argument, by confining animals to the surfaces of their cave walls, the artists believed they were bringing the beasts under their control. Some have even hypothesized that rituals or dances were performed in front of the images and that these rites served to improve the hunters' luck. Still others have stated that the painted animals may have served as teaching tools to instruct new hunters about the character of the various species they would encounter or even to serve as targets for spears. By contrast, some scholars have argued that the magical purpose of the paintings was not to facilitate the destruction of bison and other species. Instead, they believe prehistoric painters created animal images to assure the survival of the herds Paleolithic peoples depended on for their food supply and for their clothing. A central problem for both the hunting-magic and food-creation theories is that the animals that seem to have been diet staples of Old Stone Age peoples are not those most frequently portrayed. At Altamira, for example, faunal remains show that red deer, not bison, were eaten. Other scholars have sought to reconstruct an elaborate mythology based on the cave paintings, suggesting that paleolithic humans believed they had animals ancestors. Still others have equated certain species with men and others with women and found some sexual symbolism in the abstract signs that sometimes accompany the images. Almost all of these theories have been discredited over time, and art historians must admit that no one knows the intent of these paintings. In fact, a single explanation for all Paleolithic murals, even paintings similar in subject, style, and composition is unlikely to apply universally. For now, the paintings remain an enigma."

The Birth of Writing?

Spotted horses and negative hand imprints, wall painting in the cave at Pech-Merle, Lot, France, ca. 22,000 B.C. Approx 11' 2'' long.

Although we cannot say for sure exactly what the paintings mean or what they stand for, it is unquestionable that they had some level of significance. Right by the cave paintings themselves, are some more markings. they look like dots, squares, checks and arrows. Some archeologists believe that this is the first form of writing ever experienced by man. Another reoccurring symbol is a hand print, both positive and negative. A positive hand print would be when an artist would dip his hands in ink, then pressed it against a wall. A negative hand print is when an artist would press his hand to the wall, then use the pigments around it, much like a stencil. the meaning of these hand prints, just like the meaning of the paintings they adorn, are yet unknown.

The "Running of the Bulls" at Lascaux

Probably the most famous Paleolithic caves are the ones at Lascaux. Many of the painted chambers are located deep within the cave and lead to- the Hall of the Bulls.

Hall of the Bulls (left wall), Lascaux, Dordogne, France ca. 15,000-13,000 B.C Largest Bull approx. 11'6'' long. There are depictions of many animals, mostly bulls, drawn differently, some in black figure (silhouette) and others in red figure (outline) were painted a dozen millennia later. Another feature of the Lascaux painting that deserves attention is the depiction of some bulls. the way the artist represented their horns is in a way that art historians call twisted perspective. It is 'twisted' because viewers see the head in profile, but the hors from the front. thus, the artists' view is not so strictly optical, or seen from only one side.

Aurochs, horses, and rhinceroses, wall painting in Chauvet Cave, Vallon-Pont d'Arc, Ardeche, France ca. 30,000-28,000 B.C Approx. half life size

Paleolithic Narrative Art?

Rhinoceros, wounded man, and disembowled bison, painting in the well, Lascaux, Dordogne, France, ca. 15,000-13,000 B.C Bison approx. 3' 8'' Long.

This is one curious piece of art. To the left of this painting is a rhinoceros, with two rows of three dots behind it with an unknown meaning. To the right we see a disemboweled bison, crudely painted, yet the artist captured the bristling rage of the animal, whose bowels are hanging out in a heavy coil. In the center there is a bird-faced (masked?) man, one of the first times a male was portrayed. His position is ambiguous, is he wounded, dead or tilted back and unharmed? Do the staff (?) with the bird on top and spear belong to him? Was it the rhinoceros or the man who disemboweled the bison? If these figures were painted to depict a collection of events or a story, then this would be classified as a narrative. Like most paintings in cavern walls, the meaning is still hidden within the fading brush strokes.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment