The Ice Recedes

At about 9,000 B.C, people began to settle down into the Mesolithic Era. The ice that covered much of Northern Europe began to melt. Geographically, climatically and biologically the changes during this period transformed the world from the time of the cavemen to the world of today. In the Paleolithic Era, the people had learned to abstract their world by making pictures of it, most likely an attempt at controlling the environment. In the Neolithic period, humans became more capable of actually controlling their world. What separates each different area are advancements in technology. The Paleolithic Era was marked by food gathering, and simple food production. The Mesolithic Era was reminiscent of intensified food gathering and the taming of the dog. Finally, the Neolithic Era was marked by the beginning of agriculture and stock raising. This new period made its first appearance in the Near East.

Ancient Near East

The Dawn of Civilization

Traces of human life have been found in the grassy uplands bordering river valleys. THese regions provided the peoples with conditions that jump started the development of agriculture. Plants such as wheat and barley were plentiful, along with herds of goats, sheep and pigs-animals that were easily domesticated. There was also a favorable amount of rainfall for raising crops. The Neolithic people were the pioneers of government, law, religion, writing, measurement, calculation, pottery, metal working and weaving.

A Stone Tower Ten Thousand Years Old

By 7,000 B.C agriculture was well under way in the Near East. Although no food remains were found, the rise of towns such as Jericho is proof enough. Jericho is located in a plateau in the Jordan River valley with a spring and was occupied at 9,000 B.C. A thousand years later, the village underwent development when a new Neolithic town was built. Its houses sat on round stone foundations and had roofs of branches covered in earth. As the town grew and powerful neighbors established themselves, a need for protection presented itself. By about 7,500 permanent stone fortifications were built.

In Neolithic paintings, human themes and concerns and action scenes with humans dominating animals are central. In the Catal Huyuk hunt, the group of hunters, an organized hunting party shows a tense exaggeration of movement and a rhythmic repetition of basic shapes. The painter took care to distinguish important details such as bows, arrows, garments and heads. This Neolithic painter placed the head in profile for the same reason their Paleolithic ancestors depicted their subjects in profile-fore the informative view. Here, the torso is presented from the front, again the most informative view point. The legs and arms are then portrayed from the profile. This composite view of the human body is artificial, because the human body cannot make an abrupt ninety degree shift at the hips-and yet it is descriptive in what a human body looks like. A composite view or twisted perspective was preferred by artists until 500B.C when the Greeks rejected it. The technique of painting also evolved drastically since Paleolithic times. The pigments were applied with a brush to a background of white plaster. The preparation of the wall surface in it strikes contrast to the direct application of pigment to rock. This was another step toward easel painting with a frame that defines its limits.

The First Landscape?

The painting at one of the shrines of Catal Huyuk is considered the world's first landscape, or a work of art depicting a scene in nature with no story.

At about 9,000 B.C, people began to settle down into the Mesolithic Era. The ice that covered much of Northern Europe began to melt. Geographically, climatically and biologically the changes during this period transformed the world from the time of the cavemen to the world of today. In the Paleolithic Era, the people had learned to abstract their world by making pictures of it, most likely an attempt at controlling the environment. In the Neolithic period, humans became more capable of actually controlling their world. What separates each different area are advancements in technology. The Paleolithic Era was marked by food gathering, and simple food production. The Mesolithic Era was reminiscent of intensified food gathering and the taming of the dog. Finally, the Neolithic Era was marked by the beginning of agriculture and stock raising. This new period made its first appearance in the Near East.

Ancient Near East

The Dawn of Civilization

Traces of human life have been found in the grassy uplands bordering river valleys. THese regions provided the peoples with conditions that jump started the development of agriculture. Plants such as wheat and barley were plentiful, along with herds of goats, sheep and pigs-animals that were easily domesticated. There was also a favorable amount of rainfall for raising crops. The Neolithic people were the pioneers of government, law, religion, writing, measurement, calculation, pottery, metal working and weaving.

A Stone Tower Ten Thousand Years Old

By 7,000 B.C agriculture was well under way in the Near East. Although no food remains were found, the rise of towns such as Jericho is proof enough. Jericho is located in a plateau in the Jordan River valley with a spring and was occupied at 9,000 B.C. A thousand years later, the village underwent development when a new Neolithic town was built. Its houses sat on round stone foundations and had roofs of branches covered in earth. As the town grew and powerful neighbors established themselves, a need for protection presented itself. By about 7,500 permanent stone fortifications were built.

Great stone tower built into the settlement wall, Jericho

ca. 8,000-7,000 B.C

The 2,000 inhabitants surrounded themselves with a wide, rock-cut ditch and a five-foot-thick wall. Into this was was built a stone tower, twenty eight feet high. Not enough is known about this tower, except that it was a technological achievement, considering the tools that were available at the time.

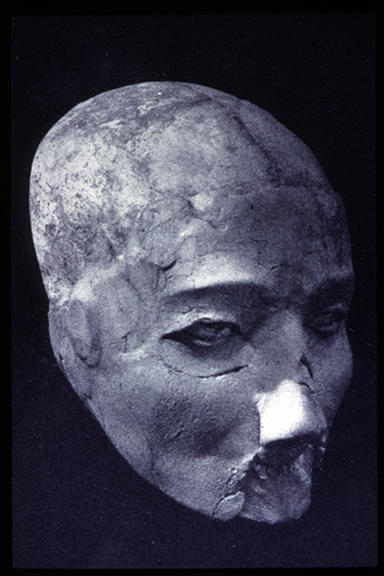

Skulls with Restored Faces

By 7,000 B.C new settlers arrived in an abandoned Jericho site. They brought a culture along with them, making shrines and statuettes of women, goddesses and animals. Most unusual is a group of human skulls reconstructed in plaster, modeled to appear life like

Human skull with restored features, Jericho

ca. 7000-6000 B.C

Features molded in plaster, painted, and inlaid with shell. Archeological Museum, Amman

They contain seashells for eyes and painted hair. These groups of skulls aren't portraits, per say-for they depict generic features. Because these heads were divorced from the body, reconstructed in plaster and buried separately, archeologists believe that the people of Neolithic Jericho must have attached a special importance to the heads. Some scholars believe they are somehow connected to a belief in an afterlife. These heads, however, mark the beginnings of monumental sculpture in the ancient Near East.

A Neolithic Town With No Streets

Excavations at Hacilar, Catal Huyuk, Anatolia show that the central Anatolian plateau was the site of a flourishing Neolithic culture between 7,000 and 5,000 B.C. The source of Catal Huyuk's wealth was trade in obsidian, a stone highly valued by tool and weapon makers alike. Like Jericho, Catal Huyuk seems to have been one of the first experiments in urban living. The regularity of its plan suggests that the town was built according to some predetermined scheme. Another peculiar feature is the settlement's complete lack of streets.

Schematic reconstruction drawing of a section of Level VI, Catal Huyuk, Turkey

ca. 6000-5900 B.C (after J. Mellaart).

The adjoined houses had no doors. There were openings on the roof that served as a means of entering and leaving the house, as well as some kind of ventilation. The attached buildings were more stable than freestanding structures, and formed a perimeter wall well suited to defense against natural of human forces. A variation of this type of building is the shrine. the shrines, when compared to houses, are more richly decorated with wall paintings, plaster reliefs, animal heads and bucrania (bovine skulls), statues of stone or terracotta.

Hunting Deer in Neolithic Turkey

Hunting undoubtedly still played an important part in the early Neolithic economy, and as a food source. The significance of hunting was even apparent in paintings. What is surprising is the regular appearance of humans in their art works.

Deer hunt, detail of a copy of a wall painting from Level III, Catal Huyuk, Turkey

ca. 5750 B.C

The First Landscape?

The painting at one of the shrines of Catal Huyuk is considered the world's first landscape, or a work of art depicting a scene in nature with no story.

Landscape with volcanic eruption (?), detail of a copy of a wall painting from Level VII, Catal Huyuk, Turkey

ca. 6150 B.C

This painting is created at about 6150 B.C In the foreground is a town, with the rectangular houses neatly laid out side by side. Behind the town appears a two peaked mountain. Art historians believe the dots and lines issuing from the higher of the two caves represent a volcanic eruption. They have also identified the mountain as the Hasan Dag. Since the painting was located in a shrine, historians believe that the eruption had some sort of religious meaning,the mural may not be a pure landscape. The findings at Catal Huyuk give the impression of a prosperous and orderly society. The conversion to an agricultural economy had been completed by about 5700 B.C

Western Europe

A Neolithic Astronomical Observation

Whereas in the Paleolithic Era, in Western Europe, where paintings and sculptures were widely seen, no great achievements in europe could compare to those found in the Near East. However, at about 4,000 B.C, the local Neolithic peoples developed a monumental architecture employing massive rough-cut stones. Some stones, exceeding ten feet high and fifty tons are called megaliths, hence the culture that crated them are considered megalithic. These megaliths are sometimes found arranged in a circle known as a cromlech or a henge, often surrounded by a ditch. The most imposing today, is Stonehenge.

Stonehenge, Salisbury Plain, Wiltshire, England, aerial view

ca. 2550-1600 B.C Circle is 97' diameter; trilithons approx. 24' high

Located on the Salisbury Plain in Southern England, Stonehenge is a complex of rough-cut sarsen, a type of sandstone, and bluestones, or volcanic rock. The Outermost ring is made of large monoliths of sarsen capped by lintels, or a stone beam, used to span an opening. Next, there is a ring of blue stones which circle a horseshoe, open facing East, of trilithons, or three stone constructions. Five lintel topped pairs of the largest sarsens. Standing apart to the East is the heel stone which marks the place the sun rose at the midsummer solstice. Like most artifacts found at so early a dat, it is not known for sure what the exact purpose of Stonehenge was. It seems to be some kind of observatory. However, as impressive as this prehistoric achievement is, at around the same time in other places around the world, civilizations were flourishing. In Mesopotamia, people had been building multi-chambered temples on huge platforms. In Egypt, the great stone pyramids were already many centuries old. These civilizations already had a written history, and that is our next destination.